Workhouse Work

This time we have combined two months as they fit in with a theme of the new poor law and workhouses, which we explore in our March lunchtime talk.

For some the workhouse was home from an early age. Our first document relates to 12 year old Eli Smith of Woburn. Eli, an orphan and inmate of the Woburn workhouse, had been appointed as errand boy to the workhouse porter and therefore had more freedom than other inmates to come and go as he pleased. These errands included going out to get meals for the clerk to the guardians and snuff for other inmates.

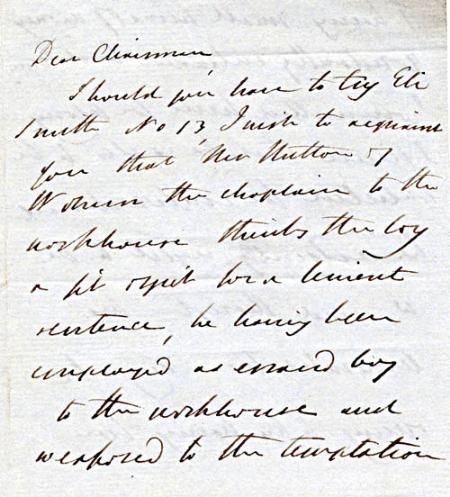

Unfortunately Eli was not as trustworthy as the masters had thought and being given money with which to run errands proved too much of a temptation for him. In 1843 he was accused of theft and on further investigation it became apparent that he had embezzled money on many occasions. It was decided that he should be prosecuted for the theft and at least one case of embezzlement as the justices were not completely without hope for Eli and thought that "if he be found guilty has such a sentence as may ensure his being sent to the Penitentiary in the Isle of Wight …In the hope he may be reformed instead of being again turned adrift after a short imprisonment." [QSR1843/3/5/13/b]. In a letter Charles J F Russell, the committing magistrate, tells T C Higgins, Vice Chairman that "Though his criminalisation may be owing to his having been exposed to unnecessary temptation it appears to be so complete as to make him a fit subject for Parkhurst and I think that imprisonment there would be the best chance of ultimately saving him". [QSR1843/3/5/13/c].

QSR1843/3/5/13c – the vicar requests a lenient sentence because Eli was exposed to temptation.

Eli was sentenced to 7 years and according to the gaol register was sent to Parkhurst on the 12 August 1843. Unfortunately this was not the end of Eli's criminal career. In 1851 he was back in Woburn and John Morris, out of charity, took him in to a room in Chapel Street so that he did not need to live on the street. He had known his friends for some time and so took a chance on him. After about 10 days Eli left without saying he was going, and after he had gone John missed a pair of boots, two cloth coats and a waistcoat. When arrested Eli denied the charge and was acquitted. However, less than a year later he was again arrested. This time he was accused of stealing 4s 1d from Henry Hodskins another lodger at John Morris's house. John Morris, Henry Hodskins and Eli Smith shared a room and Hodskins declared that Eli had stolen the money from his trouser pocket when they went to bed. Eli was still in bed when the constable arrived to arrest him and the money has found under his pillow. Although in the depositions the evidence this time seems less convincing than John Morris's evidence the previous autumn Eli was found guilty and due to his previous conviction was sentenced to 7 years transportation. The last we see of him is when he is discharged from Bedford prison on his way to Preston gaol.

While Eli was starting his life of crime in Woburn a little further south in Leighton Buzzard workhouse all sorts of things were going on.

At the epiphany sessions of 1842 four inmates of the Leighton workhouse, James Fanch, James Elgerton, Samuel Kempster and William Banks, were accused of theft from the Duke's Head public house at Heath & Reach. Although the porter had reported that the workhouse was locked up at 8pm it was apparently an easy thing for the men to get out of the sleeping ward and climb out over the front gates. Another inmate, Jabez Cosby, gave evidence against the men saying that he had seen Kempster and Banks get up and go out at about 1 am. He said they returned at about 4 am – in both cases he worked out the time by when he heard the rattle of train engines. Kempster, Banks and Fanch shared the beer, bacon and pork with him before hiding the remains around the house and garden. The master of the house says he searched the men's day room after he heard of the robbery at the pub and found the provisions hidden in the privies, the rafters and the garden. Jabez seems to not have been considered a reliable witness (both Banks and Fanch described him as the biggest rogue of all) and the four men were acquitted of the robbery. [QSR1842/1/5/45-48]. According to the gaol database all four men had other brushes with the law and in 1843 William Banks was transported for 7 years for stealing pickles.

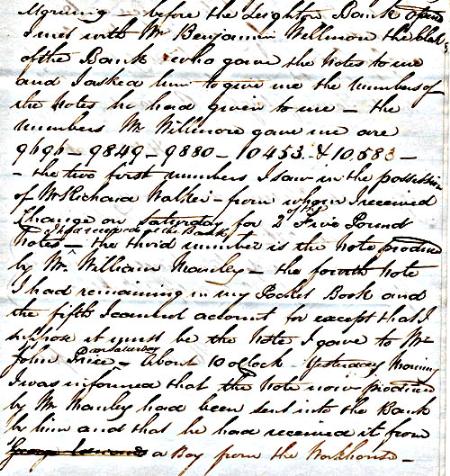

It is interesting to note that the parish constable says that rather than searching for the provisions stolen from the pub cellar he was searching the premises looking for some stolen horsehair, which makes you wonder just how much criminal activity in the area was down to the workhouse inmates. Certainly only a year later two more inmates were brought to trial. On this occasion Mr Meacher, the relieving officer, had a £5 note stolen from his pocket book, which was in his jacket hanging in his hall. He immediately suspected Robert Green aged 14, an inmate of the workhouse, who had been in the house when the note went missing as he was in the habit of being at [Meacher's] house "to clean my house, knives and shoes". The note was soon traced as another boy from the workhouse, 13 year old George Edwards, had it changed for silver by Mr Manley the grocer. Green was charged with theft and Edwards with receiving stolen goods. Both were sentenced to 6 weeks imprisonment and to be privately whipped.

QSR1853/1/5/36-37 Mr Meacher explains how the notes he received from the bank clerk were traced.

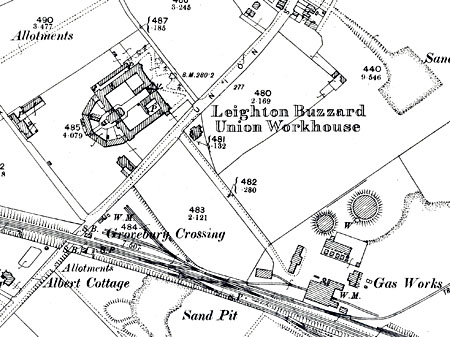

Cosby said he knew what time Kempston and Banks went out because he heard the rattle of the mail train about an hour later, from this map we can see why the trains could be clearly heard: