Cranfield after the Norman Conquest

This page was written by Sally Williams

Cranfield seems to have prospered throughout the Anglo-Saxon period and by the time of the Norman Conquest was a significant community.

In 1086 William the Conqueror conducted his survey of the 31 English counties south of the River Tees and his commissioners visited Cranfield to record the population, agricultural capability and estimated value of the estate. The survey, which became known as Domesday Book, only looked at estates and smaller holdings are therefore not recorded. Cranfield is described as being an estate of 25 households. This makes it larger than the surrounding estates of Moulsoe and Salford which had 17 households each and Holcot which had 16. Within the Redbornstoke Hundred, larger estates were found at Lillington with 46 households, Houghton Conquest with 39 and Marston Moretaine with 31.

The estate supported 18 villagers, 2 smallholders and 5 slaves. Villagers or villeins would have been farmers who held land on the estate in return for which they owed services and dues to the landowner, Ramsey Abbey. Smallholders or bordars had less land and probably shared facilities such as villagers’ plough teams of oxen. Slavery was not uncommon in Anglo-Saxon England. Slaves were considered the property of their owner and had few rights. Many were conquered native population from battles or their descendants. Later on there were many penal slaves who had been found guilty of a criminal offence. Sometimes in very hard times, individuals voluntarily submitted to sell themselves and their families into slavery in order to survive. Under the Normans, the practice of slavery started to die out. The last record of serfdom in Cranfield is in 1577 when the families of Frost and Burrell were identified as in serfdom in the era post reformation.

The Domesday Book also tells us that there was enough arable land on the Cranfield estate to provide work for 12 ploughs teams (usually eight oxen teams) of which two were operated by Ramsey Abbey and the remaining 10 by villagers. There was a further meadow for 2 ploughs and enough woodland for 1000 pigs. This is a very significant woodland resource representing possibly around 1500 acres (600 hectares) and shows that the area around Cranfield was still very heavily wooded at this time. Typically estates in the Redbornstoke Hundred were recorded as having woodland supporting between 200 and 400 pigs.

The purpose of King William’s survey was to assess the value for the purpose of taxation. Each estate is allocated a value of “geld” for taxation purposes. Each estate was assessed for value in 1066, at the time of the Norman invasion, 1070 and at 1086 when the survey was carried out. Cranfield was estimated to be worth £12 in 1066 and this fell to £9 in 1070 and remained the same in 1086. The significant decline in prosperity is thought to be associated with the considerable drain on resources for marshalling the armies to fight in the north and provisioning them for the “Harrying of the North”. Other estates which were directly in the path of the army route marches are said to have declined in value by up to 45% at this time.

Although smaller than its neighbours of Lidlington, Houghton Conquest and Marston Moretaine, Cranfield’s tax liability was set exactly the same at 10 geld units.

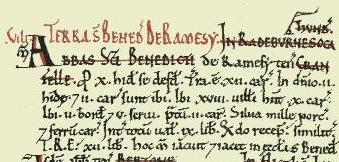

Extract from the Domesday Book for Cranfield

(Image credit: Professor J.J.N. Palmer and George Slater from Open Domesday under Creative Commons BY-SA 3.0 License)

The landscape

Under the Norman occupation, there was little significant change in the layout of the landscape. The field system remained large open fields cultivated in strips creating ridges of land known as selions. The plough teams worked in a clockwise direction such that the soil was always turned to the right. This resulted in the soil heaping up in the centre with a small ditch either side. Visible remains of this form of agriculture remain as ridge and furrow and examples exist in the parish. The parklad behind The Lodge in Lodge Road is a good example and clearly shows ridge and furrow. Other examples have been identified on the land where the Home Farm development now stands, land south of Cranfield airfield, north of the High Street, Rings Wharley Farm, Manor Farm, Moat Farm, Mill Road and Gossards Green. [Heritage Environment Record 4431]

Medieval fields were governed by common rules of cultivation and grazing, usually decided upon by an assembly of the tenants at the manorial courts. Today's fields are really 'closes', enclosed land in single ownership.

Expansion of the Arable

As population increased during the 12th and 13th centuries so more land was required for agriculture. The common fields on the plateau were insufficient so 'assarting' (woodland clearance) became widespread in the ring of woodland around the plateau in order to expand the area of arable.

Evidence of assarting or of land newly brought into arable cultivation is plentiful in a manorial 'extent' (survey) of 1135. This describes the manorial estate, listing the demesne lands and property, including its stock, crops and income, and all the tenants, their holdings and the rents and services due from them. At this time, several tenants held assarted land as well as their other long established 'tenements' (holdings).

Extensive piecemeal clearance is indicated and in the second half of the 12th century some 350 acres of assarts were held by about 30 tenants for money rents. This proliferaton of small holdings in the woods brought a tremendous increase in manorial rents during the 12th century; this meant extra income for Ramsey Abbey, the manorial overlords, who probably actively encouraged assarting. Mention of demesne assarts shows that Ramsey Abbey were involved themselves as were all the other levels of society, both freemen and peasant tenants. All were individually clearing and enclosing land with the hedges and ditches that are often mentioned in the documents. Several references to "new assarts" in another manorial survey of the early 13th century show that clearance was continuing then as it did throughout the rest of that century.

The village takes shape

The historic core of what is now regarded as the village of Cranfield lies on the plateau, close to its south eastern edge. It was established by the early 12th century and was originally known as Town End. End is a term usually used to denote a particular part of a parish, not necessarily a settlement, whilst town in its medieval sense refers to a village. Town End therefore means that part of Cranfield parish in which the main village lies. The whole area was originally called Cranfield, and that name only later became attached to what is now the modern village.

At the west end of the village was the settlement of Wood End which was located at the junction of modern-day Court Road and Lodge Road including Bury Farm (now known as Home Farm), Wood End Road and Doeswell Lane (now the drive to The Kennels). Alanum de Woodende is listed as living here pre-1244.

All was not peaceful; however, as in 1144 during the civil war between King Stephen and Queen Matilda, King Stephen’s forces pillaged the village.