The Manor of Dixwells

This article on the Manor of Dixwell was written by Chris Schuster

Dixwell’s Manor probably took its name from Robert Dykeswell, who came to the Manor in Tingrith through his wife Agnes. Agnes was the widow of Edmund Pecok, whose father John Pecok was named as Lord of Tingrith in 1332 in the list of Tingrith Rectors. John Pecock originated from Redbourn [Hertfordshire], but probably lived at his manor of Windridge, Saint Albans [Hertfordshire]. It is unlikely that he ever lived in Tingrith, and it is possible that there never was a manor house associated with Dixwell’s as the lords of Dixwell’s Manor all had residences elsewhere. The manor could easily be run by a bailiff from a farm.

Robert Dixwell was Member of Parliament for Bedfordshire from 1383-1388 and also Sheriff of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire in 1384-5, when he was described as ‘Robert Dixwell, seat Tingrey’. Certainly, by the date of his first return to Parliament in February 1383, Dixwell had established strong connections in Bedfordshire, and over the next few years he became closely involved in the local community. In 1385, for example, he was made a trustee of an estate in Westoning and he also acted as a feoffee of land in Chalgrave.

As a young man in Cambridgeshire Dixwell had acquired a reputation for crimes of violence and although a figure of some consequence in Bedfordshire, he evidently felt no more respect for the law than he had as a youth. In 1384 he was again summoned before a court, this time because of an assault allegedly made by him and his men on the Earl of Buckingham’s property in Buckinghamshire. Notwithstanding this brush with the youngest of Richard II’s uncles, Dixwell was made Sheriff of Bedfordshire and Buckinghamshire in the following November; and just one day after his appointment he took his seat in the House of Commons for the third time (thus technically contravening the statute which forbade the return of sheriffs to Parliament).

de Grey coat of arms

The de Grey family acquired the overlordship of one if not two manors in Tingrith at the beginning of the 15th century and certainly held Dixwell’s Manor as overlords in 1509 when Richard de Grey, 3rd Earl of Kent, heavily in debt, probably through gambling, listed it in the manors that were sold to Henry VII (1485-1509) to pay off his debts. The following year Richard was a sword-bearer at the coronation of the new king, Henry VIII (1509-1547), who granted the manor back to the earl. In 1520 Richard accompanied the king to his meeting with King Francis l of France at the Field of Cloth of Gold, where he was accompanied by three chaplains, six valets, thirty three servants and twenty horses. Richard’s continuing taste for the high life resulted in debt and the manor reverting back to the Crown after his death in 1524.

The Field of the Cloth of Gold, oil painting of circa 1545 in the Royal Collection at Hampton Court

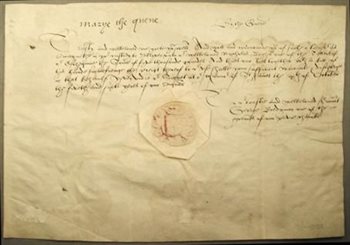

In 1554 Mary I (1553-1558) granted Dixwell’s Manor to ‘a grome of the privie chamber’, George Bredyman, for twenty one years and made the grant permanent two years later when George married one of her chambermaids.

Grant by Mary I to George Bredyman

George went on to become the keeper of the Palace of Westminster under Elizabeth l (1558-1603) who, in 1574, leased Eversholt Manor to him for sixty years at a rent of £31 11s. 5d. He died in 1581 and in 1600 his son Edmund, being in considerable debt, alienated (sold with special licence of the overlord) Dixwell’s to Robert Hodgson.

Brass of Robert Hodgson in the church

In his will of 1611 Robert Hodgson left Dixwell’s Manor to his debtor William Ashton, in lieu of money he owed to Ashton. However, the day after he made his will Hodgson also used the manor as security to borrow money from Thomas Roupe and Leonard Welstead, so that when Robert Hodgson died there were three people claiming the manor.

In 1618, Rowe and Welsteed were named as Lords of the Manor on the Court Roll. The manorial court had wide legal jurisdiction over the inhabitants of the manor, sometimes with the right to administer capital punishment, if, as in Tingrith’s case, the lord had obtained from the king the right to hold a court leet. Much of the law was specific to a particular manor, as developed by "custom of the manor" and as interpreted by the manorial court. In the Court Roll of 1618 many of the villagers were fined for grazing their animals at the wrong time (before the hay was taken in) or in the wrong place. It was also noted there had been no metes in the village for a year and everyone was ordered to attend a mete and see the bounds or pay 12s to the lords.

William Ashton who had expected to inherit the manor was a local man being the son of Robert Ashton of Woburn, a gentleman of the horse to the Earl of Bedford. William was in the service of King James l’s chief minister, Robert Cecil, the 1st Earl of Salisbury (who built Hatfield House) and William became MP for Hertford and later Appleby [Westmorland], receiving a knighthood in 1628. Although he had court connections he actively supported Parliament in the English Civil War. He became a Presbyterian Elder and bought the advowson of Tingrith from the Roman Catholic Earl of Cleveland in 1642, meaning he had the right to appoint the Rector of Tingrith. He drew up his will on 16th February 1646, leaving £20 to the poor of St. Martin-in-the-Fields [Middlesex], to be distributed ‘as my wife shall think fit, provided she be careful not to dispose of it to undeserving beggars’.

Eventually, the manor was settled on William Ashton’s son when he married, and William’s granddaughter, Mary Ashton, who had married Sir John Buck, High Sherriff of Lincolnshire, inherited Dixwell’s Manor after the death of her father, also William, and uncle, Robert. The manor then remained in the Buck family until 1724 when Mary’s grandson, Sir William Buck, together with Frances his wife, made a settlement of the manor in 1697. William was succeeded by his son, Sir Charles Buck in 1717, who recovered the manor in 1720.

Buck family arms

Four years later Sir Charles conveyed the manor for £1400 to prominent Woburn resident and solicitor, Ambrose Reddall. Ambrose Reddall’s son, Richard, passed Dixwell’s and other property to his son, another Ambrose, on his marriage. The marriage settlement of 1737 refers to rents and payments previously made to the Earl of Cleveland, and to adjoining land previously belonging to the late Sir P Chernock and then to David Willaume, i.e. Tingrith Manor. The manuscript memoirs of a Mr. Cole, now preserved at the British Museum is an account of his visit to Mr. Reddall of Eversholt in 1767, with the following description: 'The house, grounds and fish-ponds are singularly neat and elegant. He has such an abundance of water, and that contrived so artfully, that you may see two pretty cascades from the windows, and what is more singular, his kitchenjack is turned by an overshot watermill.' Unfortunately it is more likely that the above-described house was situated at Wakes, Eversholt rather than Tingrith!

In 1765, Dixwell’s Manor was sold to Edward Willaume, then Lord of Tingrith Manor, for £3700. Dixwells at that time consisted of:

- 6 messuages (dwelling houses with outbuildings and land assigned to their use);

- 6 tofts (homesteads);

- 120 acres of arable land;

- 20 acres of meadow;

- 120 acres of grazing;

- 5 acres common land.

The manors of Tingrith were reunited and in 1790, when a Court Leet was advertised to be held at the Manor House Tingrith, Edward’s widow, Essex Willaume, is referred to as the Lady of the Manors of Tingrith and Dixwell’s. Without a manor house to carry on the name, Dixwell’s is rarely referred to again after this time.