Bedford Castle

Imaginative view of 'Bedford Castle at the time of the Great Siege, 1224' [Z251/306/25]

It is not known when the Norman castle at Bedford was built. The town had defences during the Anglo-Saxon period. The castle is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 but as the survey was primarily concerned with making an assessment of landholding for taxation purposes this does not prove that a castle was not in existence (absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!). It was built on the site of the Anglo-Saxon defences north of the river and may even have included some of them. It was a classic Norman fortification of a mound, or motte, on which were wooden, later stone, defences, surrounded by an area of dwellings, armouries, stables and so on called the bailey. There were, in fact, two baileys, an outer one and, separated from it by a wall, an inner bailey which would, no doubt, have contained the lord’s own hall, the chapel and other such buildings. The motte then lay inside the inner bailey, giving three defensive rings to the whole structure. Ditches, at some point lined in stone, lay immediately outside each length of wall.

It is possible that the castle was built shortly after the Conquest but the first mention of it is in 1138 when Milo de Beauchamp held it on behalf of Matilda against Stephen during their civil war which was eventually resolved in Stephen being king but his successor being Matilda’s son, Henry, later Henry II. De Beauchamp lost the castle to Stephen but recovered it shortly afterwards. The castle was described at that time as: “completely ramparted around with an immense earthen bank and ditch, girt about with a wall strong and high, strengthened with a strong and unshakeable keep” [Rolls Series in The National Archives, 1886, 30-32].

The top of Bedford Castle motte May 2009

The castle may have been besieged in the early 1150s as the Pipe Roll for 1157/8 records a payment of twenty marks to the King from the burgesses of Bedford who “were in the castle against the king). The Sheriff of Bedfordshire paid small sums for maintenance [Colvin, 1963, II, 558] - £4/10/1 in 1880, £12 in 1883 and £4/6/- in 188 for work on the bridge and postern gate of the castle facing the river. The Pipe Roll for 1205 records 13/9 spent on repairs to the prison within the castle.

A ruthless Norman mercenary, Faulke de Breauté, a prominent vassal of King John (1199-1216) captured Bedford Castle in 1215. He had served John on the Welsh Marches since 1206 and when the barons rebelled against John in 1215 de Breauté stayed loyal. He captured the castle at Hanslope in Buckinghamshire then took Bedford from the forces of William de Beauchamp, who had entertained the rebellious barons at the castle earlier in the year. De Beauchamp was absent during de Breauté’s brief siege. Bedford castle was given to de Breauté by the King and he began to overhaul the defences. Ralph de Coggeshall says that he: “strengthened and expanded the castle at great expense, fortifying it with towers and outworks and a variety of warlike machines. He pulled down to the foundations the great church of Saint Paul which from antiquity had stood next to the castle, and the church of saint Cuthbert, and with the stones of the churches he built towers, walls and outer walls, and surrounded it on all sides with deep paved ditches”.

Bedford Castle motte May 2009

Bedford Castle motte May 2009On John’s death de Breauté continued his royal service with John’s nine year old son, Henry III (1216-1272). He was made High Sheriff of Bedfordshire, Buckinghamshire, Cambridgeshire, Northamptonshire and Oxfordshire and defended the area against the invading army of the heir to the French throne, Prince Louis (late Louis VIII) who had been invited by the barons to become King of England. Louis seized Hertford and Cambridge from de Breauté in 1217. Worcester had been sacked by de Breauté in 1216 after siding with the barons, now he sacked Saint Albans [Hertfordshire] for siding with Louis. He also attacked Warden Abbey, no doubt to seize the treasures it held.

At the Battle of Lincoln in 1217 de Breauté’s crossbowmen stormed the gate of LincolnCastle, playing an important part in the defeat of Louis’s forces. That Christmas he entertained the royal court at Northampton. He added more castles to his portfolio but many of the prominent nobles of the land were his enemies, principally the Chief Justice, Hubert de Burgh. In November 1223 de Breauté, along with the Earls of Chester and Gloucester, revolted against de Burgh’s rule. The revolt was short-lived and a peace was negotiated, de Breauté losing all his shrievalties by January 1224. He was then ordered to give up Bedford Castle along with a castle at Plympton [Devon], which he refused to do; he was then charged with breach of the peace and held a justice sent to investigate the charge as a prisoner.

One of the stones marking the perimeter of the tower on Bedford Castle motte May 2009

On 20th June 1224 Henry III and his army besieged Bedford Castle, the Archbishop of York excommunicating both de Breauté and the whole garrison! The siege lasted for eight weeks and around two hundred people were said to have been killed. Three assaults failed but a fourth breached the barbican (defended gateway), allowing the whole outer bailey to be captured. Next the wall near an old tower (the one nearest Saint Paul’s) was breached by mining. This meant that tunnels were dug beneath the wall and filled with faggots which were set alight, collapsing the tunnel and bringing down a section of the wall with it. That meant that the inner bailey fell. Finally the keep, the tower on the motte, was also undermined and the place surrendered. De Breauté’s brother William, who had been in command, along with eighty knights were captured and hanged. Detailed accounts relating to the material for the siege engines survive and were translated by George Herbert Fowler in Bedfordshire Historical Records Society Volume V of 1920/21.

Information plaque on Bedford Castle motte May 2009

De Breauté himself, luckily for him, was not at Bedford. He submitted on 19th August and was exiled to France after losing all his lands. On his arrival Prince Louis, now Louis VIII, imprisoned him but released him the following year. He died in Rome in July 1226. The siege is chronicled in the Chronicum Anglicanum by Ralph de Coggeshall, the Annales de Dunstaplia and royal letters. Close Rolls surviving in the National Archives detail royal commands for dismantling the castle’s defences, a process known as slighting. Towers were levelled and ditches filled in. Walls were reduced significantly in height and by 1361 the site was described as: a void plot of old enclosed by walls”. And so it seems to have remained until Bedfordbegan to expand eastward during the 19th century when areas of the former baileys were used for housing.

Bedford Castle lime kiln 1979

Archaeological excavations of the castle mound and surrounding area were carried out between 1969 and 1973 under David and Evelyn Baker, the results being published in 1979 as Excavations in Bedford 1967-1977 being Volume13 of the Bedfordshire Archaeological Journal. Amongst other things a medieval lime kiln, possibly 12th/13th century in date, was found in 1972, measuring 5.5 metres in diameter to a depth of 5 metre and built of mortared stone blocks. It was infilled and became a scheduled monument. It lay just north of the now demolished Golden Eagle public house, in the northern part of the castle area. Perhaps it was made for de Breauté’s extensions to the castle from 1216 to 1224. A burial, presumed to be medieval, was also found outside the entrance to the castle.

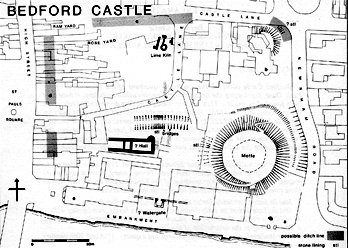

Plan showing the extent of Bedford Castle

David Baker, in the excavation report, described how later map evidence could help to determine the boundaries of Bedford Castle, shown on the plan above from his report. A ditch ran along what is now Newnham Road and is shown on Reynolds' map of Bedford of 1841. In 1804 a hexagonal militia depot was built on the slight mound at the north-east corner of the castle [see the photograph below] and foundations of what might have been a wall were discovered. To the north the outer perimeter ran east along Ram Yard. A deed of 1800 from the archive of the Duke of Bedford [R4/534/13] shows the western length of this northern ditch. It also formed the southern boundary to properties on the south side of Mill Street in the 16th century [CRT130Bed7]. The western boundary of the castle seems to have been the rear of eastern boundary of properties on the east side of the High Street rather than the High Street itself. These would have been shallow properties as the ditch line runs through the western half of the modern buildings themselves as shown on the plan above. The Ram Inn was described in 1563 as lying between The Rose and The Red Lion abutting the High Stret west and the castle ditch east [CRT130Bed7]. The southern limit of the castle was, of course, the river.

Earth work at the north-east corner in 1979

Interestingly, David Baker refers to accounts of a wall, ten feet wide, running across the river immediately south of the castle. It was designed as a dam to feed the castle moat and was mentioned by in 1851 as being partly visible at low water, in 1774 some of the upper stones had been removed to build the Howard Meeting in Mill Street.