Records of Fairfield Hospital

Insights into the Role of Family and Friends in the Care of the Mentally Ill in the Nineteenth Century: the evidence from records of the Three Counties Asylum held at Bedfordshire & Luton Archives Service by Claire Sewell

Researcher Claire Sewell used some unusual records in the Fairfield Hospital collection to study attitudes to the mentally ill in the 19th Century

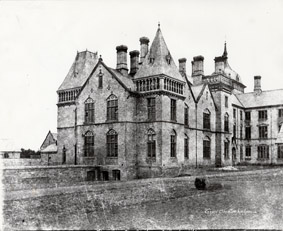

Three Counties Asylum c.1870 [Ref.Z50/2/3]

Movement towards ‘Care in the Community’ began with the 1959 Mental Health Act, which removed the distinction between psychiatric and other hospitals. Since the 1970s the care of the mentally ill has become increasingly de-institutionalised, with the vast majority of those with mental illness living within the community. This process culminated in the 1990 National Health and Community Care Act. This has been seen by some historians as a return to the state of play prior to the County Asylums Act of 1845, which required every county and borough in England and Wales to to build an asylum. Before this Act, building an asylum was optional, and the one built in Bedford in 1810 was only the second in the country.

This is in stark contrast to the sprawling, imposing image of nineteenth century county asylums, such as the Three Counties Asylum (later Fairfield Hospital) near Arlesey, Bedfordshire. However, records from the Three Counties Asylum [LF collection] suggest that this image does not reflect the whole situation. Instead, this rich resource demonstrates that an inter-play existed between families, authorities and patients, who negotiated the committal status of the mentally ill. Some patients were sporadically committed and discharged from the asylum throughout their lives, with family and friends taking responsibility for much of their care when they were not committed.

Superficially, the Three Counties Asylum supports the argument that in the nineteenth century asylums became the ‘sole, official response’ for instances of insanity. Indeed, in many ways the Three Counties Asylum seems to confirm this. The asylum opened in 1860 to replace the Bedford County Asylum and served Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire and Huntingdonshire. Between January 1871 and December 1891 the population of the asylum almost doubled, from 524 to 1015 patients [Ref.LF1/9]. This pattern is consistent with the situation in other County Asylums throughout the country, which moved further and further away from the aspiration of small asylums offering moral therapy such as those modelled on The Retreat in York.

Evidence within the vast collection of records from the Three Counties Asylum, held at BLARS, suggests that the families and friends of relatives did indeed have influence over the admission and discharge of their relatives, and that care in the community did in fact occur during the nineteenth century.

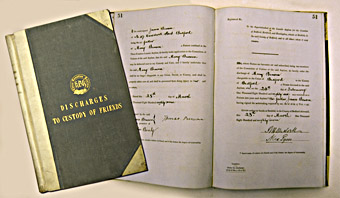

The Three Counties Asylum archive includes a register entitled ‘Discharges of Patients to Custody of Friends’ [Ref. LF40], covering the period 1878-1897 . This register reveals some very interesting insights into the attitudes of friends and families towards the mentally ill during this period.

Many of the patients who were noted as relieved into the custody of friends in this register were discharged as ‘unrecovered’. This suggests that they required care after they left the asylum, which happened in their homes, or perhaps more widely in the local community. Additionally, testimonies from relatives found in patients’ case note records suggest that people were often unwell for some time before their family sought their committal.

Five of the 43 patients listed in the Discharge to Custody of Friends Register were readmitted, and subsequently re-discharged from the Three Counties asylum by friends or relatives. Of these, Susan Cunningham and George Hartley are only relieved into the care of their ‘friends’ for just over three months before they are subsequently re-committed [Ref. LF40/1]. The majority of patients listed in the register, and the majority of patients who were admitted to the Three Counties in 1871, 1881 or 1891 stayed in the asylum for less than a year [Ref. LF 27, 29, 31 and 40]. The brevity of these stays, along with the evidence that friends and family relieved patients, suggests that an ongoing relationship ensued after committal. Of particular note are the letters held within the Three Counties Asylum records from the husband of patient Mrs Pratt to the then Superintendent Mr Swaine. These letters prove that there was regular contact between the asylum and the friends and relatives of patients. Mr Pratt writes in one such letter, dated 22nd November 1893, ‘Sir, I was very sorry to have to bring my wife back to you’ [Ref. LF 29/12]. With the sporadic survival of letters in asylum archives, it is likely that this was not an isolated incident. This strongly indicates that the Three Counties Asylum was used as a space for respite for families who were willing to act as carers when circumstances allowed.

It seems that these circumstances were not limited to the financial status of the families concerned, but also on the behaviour exhibited by the mentally ill relative. When the asylum histories of the patients listed in the Discharges to Custody of Friends Register are tracked, a pattern emerges of patients who are admitted to the asylum with testimonies of friends and family members who stress the dangerous, suicidal and/or generally unmanageable nature of their affliction. For example, Mary Jane Robinet ‘threatened to set fire to buildings’ and Jessie Bower ‘wished to go into the pond’ [Ref:LF29]. Their families were unable to care for them in such a state, not because of their mental state per se, but because of the threat they posed to themselves and, on occasion, to others. It should also be noted that suicide was illegal in the nineteenth century and thus families’ of suicide victims risked losing their potential inheritance. Rendering the classification of their suicidal relative as insane via their short-term committal seemed a more favourable option.

Another patient in the Discharges to Custody of Friends sample was Jonas Abbott. His medical certificate features the testimony of his wife who ‘states that he has been suffering from melancholia for the past four years, but the last fortnight the patient is subject to violent fits of mania’ [Ref.LF31/8]. In this instance a melancholic condition was deemed to be manageable at home, whereas the onset of a manic episode required the help of the asylum.

Thus, this implies that the mentally ill were often cared for in the communities surrounding the Three Counties Asylum, until their conditions became more severe, or if there was a sudden change in behaviour. For some, these periods of unmanageability were best treated in a controlled environment.

Recent studies of the relationship between families and asylums, conducted for example by Andrew Scull and Akihito Suzuki, have moved away from the use of asylum records, in response to the difficulties with extracting the familial voice from them, as they usually employ official discourse. However, this study has shown the continued value and of asylum records, especially for Pauper Asylums. The Three Counties Asylum’s Discharges to Custody of Friends Register, along with letters from relatives, has shed new light on this issue proving that families played a key and continuous role in their relatives’ lives before, during and after their committal to the Three Counties Asylum.

The records for the Three Counties Asylum, along with the other nineteenth century county asylums across the country still have a lot to offer in terms of grasping a better understanding of how mental illness was responded to at this time.

The Three Counties records indicate that care in the community is not a phenomenon which has come and gone, and come back again, in the history of mental illness, but rather it has always been a strategy to deal with mental illness, although it has afforded differing degrees of prominence over time.