The first Education Act was passed in 1870 (more correctly it was known as the Elementary Education Act). It was a milestone in the provision of education in Britain demonstrating central government's unequivocal support for education of all classes across the country. It also sought to secularise education by allowing the creation of School Boards. These were groups of representatives, elected by the local ratepayers and the Board had the powers to raise funds to form a local rate to support local education, build and run schools, pay the fees of the poorest children, make local school attendance compulsory between the ages of 5 and 13 and could even support local church schools, though in practice they replaced them, turning them into Board run schools (known as Board Schools).

![James O'Neill [P85/28/4/25]](/CommunityHistories/Luton/LutonImages/P85-28-4-25 James ONeill.jpg)

James O'Neill [P85/28/4/25]

When the act was passed Luton had two National Schools - in Queen Square and Stopsley and a British Free School in Langley Street. This was obviously too small a number for a growing industrial town like Luton and the new act promised a way in which to build these schools - form a school board and raise money. For the most part the Nonconformists in Luton (Baptists, Methodists, Congregationalists and Quakers for the most part) were willing for a School Board to be formed and were happy for the British School to be handed over to it. The Vicar of Saint Mary's, James O'Neill thought otherwise, wishing education to remain largely in the hands of the Church of England and stating that funds could be raised to build enough new National Schools. The result was that funds were raised to build National Schools in Buxton Road and Havelock Road named after the churches in whose parishes they fell, Christ Church and Saint Matthew's respectively. The building of a school in High Town was not an entirely new development as a school for boys and infants had been created in a wooden church building in High Town in 1870 and some girls had attended ‘The Iron School’ (held in a corrugated iron building) since 1864.

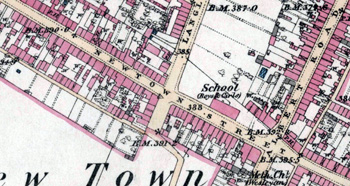

The site of New Town Street School on an Ordnance Survey map of 1880

James O'Neill himself largely financed another school in New Town Street. New Town Street opened in 1873 and the other two in 1874 but by then the argument had been lost. Though a poll in 1871 defeated the idea of a School Board by 493 votes to 1,196 the Board of Education in London were not satisfied that there were enough schools and an Order was signed on 27th January 1874 to set up a School Board in Luton.

The first election saw five candidates, led by James O'Neill who could be categorised as representing the Church of England (they were known as the Prayer Book Five) set against five other candidates, four of whom were nonconformists and one the Vicar of Biscot, who wanted a school built for his parishioners (these were known as the Bible Five). The result was that although O'Neill came top of the poll, all the members of the opposition five were also elected. O'Neill tried to have the elections set aside as undemocratic but failed. The first chairman was a Quaker, William Bigg, whose first act was to make education for both sexes compulsory in Luton for all aged five to thirteen. Parents paid two pence a week to have their children educated, free education not being introduced until 1890.

Old Bedford Road School in 1966

The Board built enough new schools for the growing population. In order of opening these were:

- Leagrave in 1875;

- Waller Street in 1877;

- Biscot in 1879;

- Chapel Street in 1880;

- Hitchin Road in 1883;

- Old Bedford Road in 1883;

- Surrey Street in 1891;

- Dallow Road in 1898

- Dunstable Road in 1898

![Waller Street with the schools in the foreground [Z50/75/108]](/CommunityHistories/Luton/LutonImages/Z50-75-108 Waller Street with the schools in the f.jpg)

Waller Street with the schools in the foreground [Z50/75/108]

In addition Langley Street became a Board School, though Queen Square, New Town Street, Havelock Road and Buxton Road remained National Schools. In 1890 the Board made a very important decision: it decided that the school in Waller Street should become a Higher Grade School. This meant that boys from all the other Luton schools would attend Waller Street if they were academically able enough - a foreshadowing of the Grammar Schools introduced in the Education Act of 1944. The Board then tried to do the same thing for girls at Langley Street but this was not a success as, unlike the 21st century when girls routinely outperform boys at secondary schools, there were not enough girls of sufficient merit to make the school viable. This is, perhaps, not surprising given that there had been no real education for girls older than infants until the mid 1870s. Once girls were old enough they were sent off to plait schools where they plaited straw as well as, supposedly, gaining a basic education. In fact they were simply earning money by their labour for the rest of their families and this attitude, no doubt, took some time to change.

A land mark Education Act was passed in 1902, coming into effect in 1903. It disbanded the School Boards and gave day to day running of education to newly formed Local Education Authorities. The old Board Schools thus became Council Schools whilst the old National, British and other non-Board schools became known as Public Elementary Schools.