Bedfordshire and the Slave Trade

The evidence in the archives

This article written by James Collett-White in 2008 concentrates on the transatlantic slave trade: the use of enslaved African people on estates owned by Bedfordshire landowners, and the contribution Bedfordshire people made to abolition. The article was edited and revised by staff in 2023.

The Slave Trade

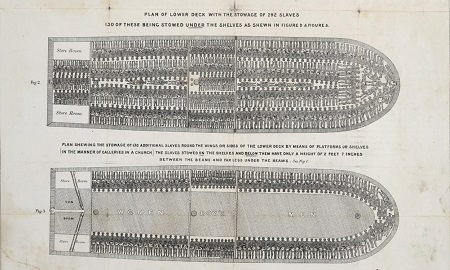

Stowage of the British slave ship "Brookes" under the Regulated Slave Trade Act of 1788 [Source: Library of Congress, USA]

The trade in enslaved people had existed in African countries and elsewhere from time immemorial. In Elizabethan times, there was a need for plentiful labour to exploit the newly discovered land in America and the Caribbean. To meet this need, the transatlantic slave trade was established.

Since 1562, ships had left Bristol and Liverpool loaded with gifts for the African princes, who agreed to the sale of some of their subjects (and captives of other tribes) into chattel slavery. Chattel slavery was a specific type of slavery, which defined African people as property who could be bought, sold, inherited, loaned and forced to work for no wages. This type of slavery was practised by white Europeans on African people between the 16th and 19th centuries. The enslaved were transported to the West Indies or America, in ships packed as tightly as possible, as shown above in the plan for the British slave ship Brookes. On their arrival, survivors would be sold for a handsome profit. The ships would then be filled with sugar, coffee or tobacco and return to Britain. Around this triangular trade grew a wealthy, powerful political group, determined to preserve the profitable business. As well as the British, the Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and French were also involved in the transatlantic slave trade.

In 1672, the Royal African Company was established to control British trade in West Africa, including slavery business. Philip Francklin, brother of John of Great Barford, worked for the Company at Cabo Corso Castle, now called Cape Coast, near Accra in modern Ghana. His letters from 1727-8 are deposited at Bedfordshire Archives [Ref. FN1055/1]. They show the business he dealt with as a Company official: too few goods to purchase enslaved workers, ships seized by the Dutch, and a war between the African kingdoms of Dahomey and Whydah. The former defeated Whydah, whose people fled. The Dahomey King proclaimed a truce, but promptly seized Whydah families and sold them into slavery.

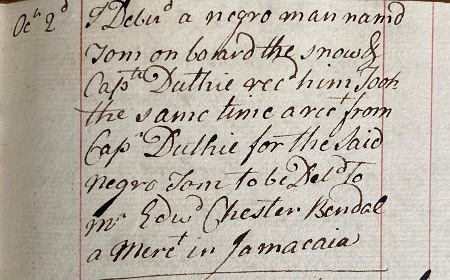

Once transported in appalling conditions, the enslaved workers were sold in America and the West Indies. Here they worked in the cotton and sugar fields whilst others worked as personal enslaved workers for landowners. Some of the enslaved workers would travel to England with their ‘masters’. Richard Antonie, who inherited the Colworth Estate in Sharnbrook in 1760, returned from Mount Cheerful, Jamaica with his ‘negro Tom’ in June 1761. Four months later Tom is sent back to Jamaica on board the ship Snow Betsy [Ref. X800/34].

Extract from the account book of Richard Antonie [Ref. X800/34]

As well as Antonie, there were at least three landowning families from Bedfordshire with estates in the West Indies, one of the most ancient of which was the Payne’s estate in St Kitts and Nevis. In 1661 Philip Payne, merchant of London, was a member of the Royal Morocco Company, when it was granted 31 years’ free trade in Africa. Most of the members of the company had interests in the West Indies and the ‘free trade’ was mainly in enslaved African people. Philip appears in the petition of the Islanders of Nevis in 1668 for redress for damage suffered during the siege of the island by the French ‘when they were reduced to eating herbs of the field boiled with salt’. In 1670 Philip and Samuel Payne, probably a brother, were listed as landowners whose estates in St. Kitts had been devastated by the French Commissioners since the Treaty of Breda.

In 1737 Prime Minister Sir Robert Walpole had Charles Payne knighted as an important member of the West Indies faction. When Payne died in 1744, he left extensive estates in St. Kitts and Nevis [Ref. BS1510]. His widow Janet was left eight enslaved workers for her personal use. A younger son, Charles, was left 55 enslaved workers to cultivate a 300 acre plantation called ‘Lowland’ ‘part being cultivated cane land and part mountainous’.

Charles’s heir Sir Gillies settled permanently in Roxton during the 1750s, buying the Tempsford manor estate in 1772 and building a new mansion there by 1794. The estates were split up on his death but the main estate in the West Indies known as the ‘Sir Gillies’ estate passed to his son John. A letter of William Woodley of St Kitts to Paynes’ agents, the Neaves, of 21st November 1803 describes the poor state of their plantations of French Point or Sandy Ground: ‘no pen, stall, windmill or any stock to carry off the canes with a horse mill’. The sick house ‘is a perfect ruin’ and ‘the negroes are notoriously the worst gang in the country from improper treatment.’ He offers to take the two plantations at a rent of 2000 guineas per year [Ref. D197].

An interesting set of accounts survive for 1823 when another Sir Charles Payne held the estate. Enslaved workers are on the same page in the accounts as ‘stock’ and their ‘increase and decrease’ is listed in the same way: 22nd July 1823, ‘Ambrose died of cramp’, on 10th August, ‘a steer died from inflammation of the bladder’. This shows how the enslaved workers were treated as property and commodities. Rum, molasses and cane sugar were the main products. All the supplies of clothing and luxury foods were imported from London. On 6th November 1815, 1122 yards of ‘Negro clothing’ (£110.9s), 8 dozen Dutch and 11 dozen Kilmarnock caps (£14.17s.6d), 15 barrels Herrings (£22.10s), 4 barrels of planters mess beer (£25) and 2 barrels of mess pork (£11) were shipped on the ‘Caroline’ for the St. Kitts estate. Medicines (£20.17s.6d) were also included [Ref. BS1538].

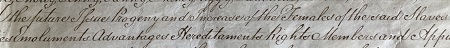

In 1771 Samuel Crawley, a London merchant and owner of Stockwood, Luton, provided a mortgage for two coffee plantations at Richmond and Digue on the island of Grenada. A list of the 74 enslaved workers survives within the mortgage deed. Included in the transaction were ‘the future issue, progeny and increase of the females of the said slaves and also nine horned cattle’ [Ref. C1521].

Extract from the conveyance, 1771 [Ref. C1521]

The St. John family of Bletsoe had a large estate in Grenada as a result of John St. John the 11th Baron marrying an heiress of Peter Simond, a Frenchman, who died in 1786. In 1826, it comprised seven separate plantations using 581 male and 535 female enslaved workers. Lists of ‘increase and decrease of slaves’ were kept: Antoine son of Marie Therese, black of Granada, was born in the Sagesse estate 26 Jan 1823. On the same estate Hannah, black, born in Africa, died of the dropsy aged 56. Caesar, born on the Island of Dominique, died aged 45 from drop[sy]. Infant mortality was high. William, aged 1 year 10 months, ‘mestiff’ in colour ‘died of fever and worms’ [Ref. J149].

Abolition of the Transatlantic Slave Trade

By 1786 there was an organised, vociferous movement in favour of abolition in Britain, supported by MPs, prominent businessmen, bishops, clergy and members of the Society of Friends. The catalyst was an anonymous article in the Morning Chronicle of 18th March 1783 stating that 132 enslaved workers had been thrown overboard alive during a voyage of an English trader in enslaved people to the West Indies. In a letter of 19th March 1783, an escaped enslaved worker, Olaudah Equiano (known as Gustavus Vassa), called for the owners of ‘The Zong’ to be prosecuted. However, he failed and the case was eventually reduced to a question of insurance. Nevertheless, a substantial opposition to the transatlantic slave trade continued.

In June 1783, a Bill was introduced to regulate the trade and on 7 July 1783 an Association was formed to discourage the transatlantic slave trade in African countries and reduce the suffering of enslaved African people in the West Indies. On 3rd November 1783 Granville Sharp wrote to Richard How of Aspley Guise, a leading Member of the local Society of Friends, mentioning how he became involved in the campaign against slavery [Ref. HW87/352]. In June 1784, the Society of Friends made a Petition for Abolition of Slavery to the House of Commons and a committee was organised to promote it.

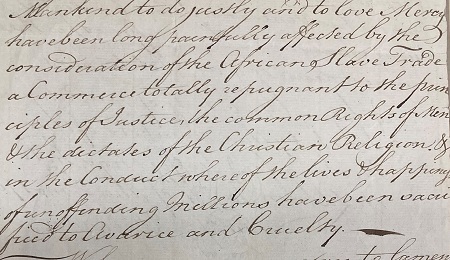

In January 1788, Richard How wrote to a number of prominent people, asking for support, including the Bishop of Carlisle, Sir George Osborn of Chicksands, Lord Carteret of Hawnes, Sir William Dolben of Finedon Hall, Northants, Sir Herbert Mackworth and Lord Eliot [Ref. HW87/396/1-10]. In reply, Osborn thought that the petition would fail, since England would suffer if other countries did not abolish the trade simultaneously. Dolben hoped that the petition would succeed [Ref. HW87/399]. He gives no clue of the central role he was going to take in the debates a few months later. Was How’s letter the challenge to his conscience that pushed him forward? A copy of the petition to the House of Commons on 4th February 1788 is in How’s archive [below, Ref. HW93/17].

Around this time Samuel Whitbread I (1720-1796) of Cardington became a supporter of abolition. His daughter Harriet Gordon’s reminiscences [Ref. W1/924-5] state: ‘I must tell you he really was the 1st Man, who mentioned the Slave Trade in the House of Commons and called Mr Pitt’s Attention to it.’

In May 1788 a serious attempt was made at abolition. In debate Sir William Dolben called for better conditions for enslaved people actually shipped, while Mr Whitbread favoured the total and immediate abolition of the transatlantic slave trade as contrary to nature, and to every principle of justice, humanity and religion. Unfortunately, it was decided that there could be no further debate on the abolition until the next year. Thomas Clarkson in his ‘History of the Abolition of The Slave Trade’ takes up the story:

‘Sir William Dolben became more affected by those considerations which he had offered to the house on the ninth of May. The trade, he found, was still to go on. The horrors of the transportation, or Middle Passage, as it was called, which he conceived to be the worst in that long catalogue of evils belonging to the system, would of course accompany it…He was desirous, therefore of doing something in the course of the present session, by which the miseries of the trade might be diminished as much as possible… till the legislature could take up the whole question...he made it known on the 21st of May in the House of Commons. He rose to move for leave to bring in a bill for the relief of those… natives of Africa, from the hardships to which they were usually exposed in their passage from the coast of Africa to the Colonies. He did not mean, by any regulations he might introduce for this purpose, to countenance or sanction the slave-trade, which… would be always wicked and unjustifiable…Mr Whitbread highly approved of the object of the worthy Baronet, which was to diminish the sufferings of an unoffending people. Whatever could be done to relieve them in their hard situation, till Parliament could take up the whole of their case, ought to be done by men living in a civilised country, and professing the Christian religion: he therefore begged leave to second the motion.’

On 2nd June 1788 Whitbread chaired the Committee of the House on the African Slave Bill. Dolben’s Bill to regulate the Transatlantic Slave Trade, seconded by Samuel Whitbread passed by vote of 56 to five and received Royal Assent on 11th July. A Bedfordshire man had been involved in getting the first statute against the transatlantic slave trade passed by Parliament. In 1792 an attempt to gain more support called for gradual rather than immediate abolition, to the sorrow of Richard How [Ref. HW87/452]. Also in the How letters are early references to the project to set up a colony for freed enslaved people in Sierre Leone in the 1790s [Ref. HW87/428&452]. This was supported by Samuel Whitbread and was led by John Clarkson.

Samuel Whitbread became convinced that, with the use of a steam engine, sugar-planting in the West Indies could be profitable without slavery. In 1789, after contacting Wilberforce, he got estimates of costs, and the following year he tried to induce the planters to buy engines. He paid for a demonstration model, designed by Boulton & Watt specially for sugar-crushing, so that planters could see a demonstration in England [Boulton & Watt Archive, Birmingham City Archives].

With the Whig Government of 1807 there was at last a real prospect of achieving the abolition of the transatlantic slave trade. Emma, Lady St John, wrote to her brother Samuel Whitbread II (1764-1815), son of the above mentioned Samuel Whitbread the founder of the brewery, and radical Whig MP for Bedford, hoping abolition would be carried [Ref. W1/4139]. The St Johns and the Crawleys were moving away from the transatlantic slave trade which had provided them with their workforce on their West Indian estates. A petition on behalf of the West Indian Planters and Merchants was sent to Samuel Whitbread II [Ref. W1/4142] with a counter blast from Thomas Clarkson [Ref.W1/4140]. The Act for the Abolition of the Slave Trade received its Royal Assent on 25th March 1808.

The Abolition of Slavery and its Impact: the evidence at Beds & Luton Archives & Records Service by James Collett-White