Tingrith School in the 19th Century

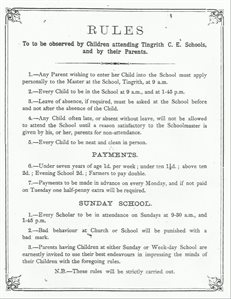

School Rules - to see a larger version please click on the image

This article was written by Chris Schister

In 1841, the three Misses Trevor paid for a school to be built in Tingrith for 80 children. In 1846/7 the Church of England made an enquiry of all its church schools. This was against the background of a new Whig government which championed secular education and the increasing importance of nonconformists, particularly Wesleyan Methodist, and Roman Catholics in providing schools. The return from Tingrith read: “There is in this parish a Sunday and Infant school, containing 65 children, of which the master and mistress are paid by the Ladies of the Manor, who wish no return to be made”.

Scholars listed as living in the village in the 1851 Census were: Charles Brittain, 13; Ralfe Brittain, 10; Joseph Short, 10; Elizabeth Brinklow, 9; William Brinklow, 6; Benjamin Brinklow, 4; George Brinklow, 2; Ann Rogers, 8; Hannah Boxford, 10; Jeremiah Sherwood, 7; Charles Sherwood, 5; Maryann Gurney, 6; Maria Gurney, 3; Charles Gurney, 5; Rebecca Gurney, 3; George Hudson, 9; Richard Hudson, 5.

Education was not yet compulsory and there were other children of similar ages in the village who were listed in the census as strawplaiters and labourers, rather than scholars.

The first Education Act was passed in 1870 and demonstrated central government's unequivocal support for education of all classes across the country. It also sought to secularise education by allowing the creation of School Boards. These were groups of representatives, elected by the local ratepayers, who had the powers to raise funds to form a local rate to support local education, build and run schools, pay the fees of the poorest children, make local school attendance compulsory between the ages of 5 and 13 (there were exceptions if children were ill, or were working, or who lived too far away, or were certificated as having reached the required standard) and could even support local church schools, though in practice they replaced them, turning them into Board run schools (known as Board Schools). The Act required a questionnaire of local schools in 1870 and the return for Tingrith simply read: “Miss Trevor’s village school. Accommodation for 87 children”.

The former school April 2009

By 1880 additional legislation meant that compulsory attendance at school ceased to be a matter for local option and children now had to attend school between the ages of 5 and 10 though some local discretion was allowed including early leaving in agricultural areas. Parents of children who did not attend school could be fined. In Tingrith a number of scholars attended school in the evening. These night scholars were mainly boys who worked in the fields during the day but still had to attend school.

The average attendance in Tingrith was 46 in 1890 and the census of 1891 showed: William S. Capell, 42, Schoolmaster; Emma S. Capell, 42, Wife, Schoolmistress. Scholars listed as resident in the village: George Shorter, 9; Walter Gurney, 9; Matilda Gurney, 8; Percy C.B. Lord, 11; Herbert E. Lord, 9; Norah Lord, 7, Minnie L. Lord, 5; Frederick Brinklow, 10; Frank M. Brinklow, 8; Laura J. Brinklow, 12; George Carr, 5; Thomas Nash, 10; Emily L. Nash, 9; Augustus G. Nash, 7; Caroline Nash, 5; Charles Roberts, 10; Louisa Roberts, 8; Lizzie Roberts, 6; Lottie A. Preston, 6; Walter Preston, 5; Victor Preston, 3; Minnie Smith, 11; Frederick W. Smith, 4; Henry Gurney, 10; Albert Gurney, 8; Rose Gurney, 5; Herbert Current, 10; Leonard A. Wheeler, 10; Arthur F. Wheeler, 8; Elsie R. Wheeler, 5.

The employment of children aged between 10 and 13 was conditional upon them having a labour certificate showing they had achieved a certain level of attainment in the three R’s. In 1893 the school leaving age was raised to 11 and older children working part time needed a labour certificate. An inspection of Tingrith school in 1893 noted that Herbert Lord, then aged 11, was absent from school but did not have a labour certificate. A few days later the log book shows Herbert was absent again, this time because he had gone to apply for a labour certificate and take the appropriate exam.

As well as children from the village and surrounding farms, the school was attended by a number of orphans from the Wandsworth and Clapham Poor Union who were boarded out in homes in Eversholt from1876 until 1901.

Victorian schools were organised by standards rather than year groups. There were six standards of reading, writing and arithmetic and promotion from one standard to another was on merit. They also pursued other, less clearly defined, aims including social-disciplinary objectives (acceptance of the teacher's authority, the need for punctuality, obedience, conformity etc).

The growth of public interest in education persuaded the Education Department to expand the curriculum of elementary schools and The Code of 1871, provided for a special grant for each individual scholar who passed a satisfactory examination in not more than two 'specific' subjects of secular instruction beyond the three Rs. In 1875, a further step was taken by the introduction of 'class' subjects - grammar, geography, history and plain needlework - for which additional grant was paid.

In Tingrith in 1879 HM Inspectors noted that in reading ‘somewhat more intelligence is perhaps desirable’ and by 1881 although the children could write, sum and sew very fairly, ‘their reading is unusually weak: they have but one set of books in each class and even this they are far from mastering.’ In 1889 the children’s reading was monotonous and counting on fingers should be checked and things were not much better in 1890 when the infant’s class could barely reach ‘fair’ in any elementary subjects.

![Group photograph taken c.1890, pupils and teachers outside the schoolroom window [Z49/765]](/CommunityHistories/Tingrith/TingrithImages/School-group-about-1890-Z49-765.jpg)

Group photograph taken c.1890, pupils and teachers outside the schoolroom window [Z49/765]

Moreover, it was also noted that no object lessons were given. Object lessons were essentially natural history and science lessons where an object or a picture of an object would be discussed. In 1892 the children sang and drilled creditably and sewing was good, object lessons were being given and the children’s answers were fairly general and intelligent despite the absence of suitable objects and pictures. Unfortunately, the Inspectors reported that the standard of Geography in Tingrith was not good enough for a grant to be awarded.

In 1895 a new schoolmistress felt lessons on manners, clothing and politeness had to be given and the curate began weekly Scripture lessons for the older children. Schemes for geography, science and detailed lists for object lessons e.g. the parts of a flower, animals, types of land, were being recorded in the school log and more detailed schemes of work produced by another new schoolmistress in 1898 resulted in a marked improvement in instruction. The following year the school was still improving although teaching was assessed as being too mechanical and science lessons needed to be more methodically prepared. Reading was fluent but the children did not seem to understand what they were reading.

The children were also expected to be able to recite large chunks of poetry. In 1890 the subject matter was quite depressing:

Standard I – II First Grief

Good night and Good morning

Standard III – IV The Graves of the Household

The Miller of the Dee

Standard V – VI The Reverie of Poor Susan

The Lighthouse

Ye Mariners of England

By 1893, Standard III is a bit better off with ‘The Village Blacksmith’, (which was certainly still on the curriculum in the 1960’s) and Wordsworth’s ‘The Daffodils’ would be a treat for Standards IV – VI, but no doubt ‘He Never Smiled Again’ would bring them back to Earth.

In 1898 cookery classes were introduced for the girls, although they seemed to be voluntary and not taken up by many of the girls who probably gained plenty of experience at home, and each girl also had a small garden patch in the playground for which they were responsible.

There were monthly visits from the Rector to check the registers and regular visits from the local Attendance Officer as well as the annual inspections of Her Majesty’s Inspectors and the Diocesan Inspectors who came to review the children’s written work and to listen to each of them recite their Catechism and Lord’s Prayer and sing. The Local School Board from Whitehall also sent a representative to assess the progress of the orphan children living in Eversholt who attended Tingrith School.

Very occasionally the Inspectors carried out spot checks. In 1900 they found that not all Standards were using paper for drawing and the gate between the boys’ and girls’ playgrounds was not locked. They pointed out that the unlocked gate had been highlighted in 1895. (As the girls’ playgrounds were divided into small garden plots there wasn’t much room left for them to play!)

The school Log Books record these visits and also the regular visits of Miss Trevor and her successors at the Manor who came to give out the prizes after the Inspections. Miss Tanqueray, the Rector’s daughter, became a regular visitor awarding prizes for good conduct and attainment and giving sweets to those who did not receive a prize. She would visit to listen to the children’s singing and sometimes bring visiting friends with her, and after moving to London on her father’s death she returned to present each child with a coronation mug in 1902. Her father’s replacement as Rector was equally generous, giving one little girl a penny for being able to tell the difference between a buttercup and a celandine.

School holidays were related to religious festivals and the needs of an agricultural community. In Tingrith a week’s holiday was given for Easter and Whitsun but only one day for Christmas, with a week’s holiday in January after the Inspection which usually took place around New Year. Half day holidays were given for religious festivals such as Ash Wednesday and Ascension Day and also for children to attend events such as the Village Feast in July and local shows such as the Woburn Flower Show and even the opening of the new Church organ in 1889. Every year, after the summer holidays, the school was closed when girls would be taken to enter their sewing in the Ampthill or Silsoe Shows. The girls’ needlework included stockings, cuffs, children’s frocks, pinafores etc. and many of them won prizes for the excellence of their work.

The dates of summer holidays varied according to the time of the harvest: usually from mid-August to mid-September but it could be as late as the beginning of September until the beginning of October if the harvest was held up by bad weather. Children would also take time off to go gleaning, picking up fallen grain. Bad weather could also cause the whole school to be closed when snow and even heavy rain prevented many of the children from attending.

Naturally, holidays were given for national events such as a royal wedding in 1884 and the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee in 1897 when as well as attending a Feast in the village, many children attended the feasts in Westoning and Eversholt too. The children sang the national anthem and gave three cheers for the King before a half day’s holiday was given on the instruction of Colonel Hanbury when Peace was declared at the end of the Boer War in 1902.

As well as the Christmas tree and presents given to the children by the Manor, by 1902 the children also received toys and cards presented by Messrs Lever Brothers and Beechams together with an orange and a packet of sweets. (Lever Bros produced cards advertising their products which could be used as greetings cards e.g. a little girl walking through the snow with a box of Sunlight soap in her basket!)

Most villagers kept a pig and Mr Capell, the headteacher from 1873 to 1895, was no different. Unfortunately, his pigs were kept very close to the boys’ toilets (offices) and when the inspectors visited in December 1893 they recorded that: ‘the smell which was very apparent on a very cold day must be offensive in hot weather. My Lords consider that the pig sty should be removed’.

The boys’ offices remained a source of concern. In 1898 the inspectors said the boys’ offices were in a foul condition and demanded they be thoroughly cleaned and repaired and the cess pits emptied. The problem was still on-going in 1902.

Childhood diseases were not preventable in those days and the whole school would be closed when epidemics of measles, mumps, whooping cough and diphtheria swept through the village. The group of orphans who lived in Eversholt but attended school in Tingrith were not allowed to attend in 1884 when diphtheria broke out in Eversholt and again in 1897 when there was scarlet fever there. The school inspectors noted that standards were affected when the school was closed for a whole month in 1889 during an outbreak of measles and in 1899 the school was closed for three weeks when diphtheria arrived in Tingrith and one of the infants died.

Accidents happened, and at least one was fatal. In 1897, an eleven year old girl climbed on the school railings at the front of the school to reach wild roses in the hedge, overbalanced and was impaled on the iron spikes, dying two hours later.

Miss Mary Trevor took a great interest in the school she and her sisters had had built in 1841. At the beginning of each year Miss Trevor would come and present prizes to the children following the inspections at the end of the previous year. After the Miss Trevor’s death, the Manor was leased out to Admiral Pechell who carried on the interest of the Manor in the school, becoming a school manager and giving the children a tea and firework display to celebrate the marriage of his daughter. When Colonel and Mrs Hanbury Barclay leased the Manor in 1894, the Colonel was a very active school manager, visiting the school frequently, and Mrs Barclay was manager for needlework, inspecting the teaching and progress and arranging for the sale of the garments made by the children to the parents. The Colonel enjoyed the hunting and shooting offered by the Tingrith Manor estate and the school was closed when the children were invited to go and see the stag or fox hunters and hounds at the Manor and some of the boys would miss school to go beating. The Colonel provided a Christmas tree and presents for the children in the Club Room, inviting the children and their parents to attend on Christmas Day, and he temporarily took over as ‘correspondent’ for the school managers when the Rector, who traditionally held the position, died, until a new Rector was appointed.