A Ramble in Elstow in 1879

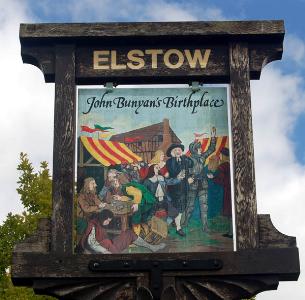

Elstow village sign September 2007

The following article, first in a series of rambles around different Bedfordshire parishes, appeared in The Bedfordshire Times on 3rd May 1879.

Elstow, Elstowe, Elennstowe, Helenstow – or whatever other orthographical variation the word is capable of – is the name of a pleasant little village which is an object of interest to others besides its inhabitants and immediate neighbours. Here was born the child whose imagination in adult years was to make him the greatest allegorist of modern times. It is impossible to be in Elstow without a thought of John Bunyan. The very grass on the pleasant old Green is classical, because there he played and laughed and “broke the Sabbath”. He has made the old Moot House on the Green a shrine to which pilgrims come from half the world. The wicket – now nailed up – in the old church door is made to do duty as the prototype of the “wicket gate” towards which Christian was directed when he began his Progress. Bunyan sat on one of the many ancient benches which still linger in the dreamy old church.

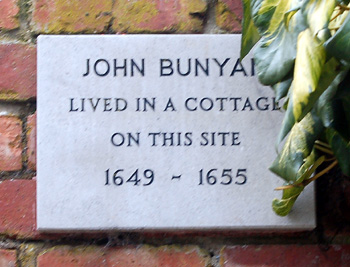

Bunyan Cottage plaque February 2012

A house bears a board on which is written “” [since demolished], a legend that on inquiry proves to be merely the perpetuation of a belief that Bunyan lived on that spot. Whatever fragment of an original “Bunyan Cottage” may remain there, the existing cottage possesses, I imagine, merely an historical-continuity kind of connexion with the hero of the village. The cottage has doubtless preserved its identity very much as did “Jack’s knife”, which first received a new blade and then a new handle, yet remained “the same knife”. But however apocryphal may be some of the mementos of Bunyan at Elstow, as of other great men elsewhere, a little hero-worship does none of us any harm. For my part I must confess to a deeply-felt sentiment of human reverence whenever I stroll across Elstow Green and think of the sturdy youth of two centuries ago, full of frolic and fun, and as unconscious of any immortal fame as are the lads who now play cricket on the same turf. There are things in the great allegory to which many of us would never subscribe, to save our lives; but the man or the woman who can read the story without being fascinated by the living picture of the human heart, of the heart’s deep daily experience, is either very prejudiced or very obtuse.

The Village Green September 2007

This paper, however, is not to be about Bunyan; and I have therefore said at the outset all I mean to say about him. I intend to write about Elstow, and will endeavour to adhere to my text. My subject is not by any means unworthy of a description for its own sake. Its beauties may perhaps be considered by some “tame and domestic”; but, true as that may be, it is rather a compliment to an English village than otherwise. For it is a very pleasant fact that the “tame and domestic” beauties of English rural scenery have inspired some of the finest passages in our poets, and are sources of perpetual delight to myriads of minds capable of appreciating the charms of nature. Apart from any associations of early life, connecting fields and flowers and hedgerows and orchards with days that had a brightness oft heir own, the sight of a grey old church and of small clusters of gabled cottages through the trees and over the hedge-tops is a very pretty one. How it harmonises with the cheery though un-rhythmical cawing of the rooks! The strokes of the smith’s hammer on his anvil, sounding to us from some hidden smithy, the whistle of a careless ploughboy, the chatter of a few children just out of school, - these and other isolated sounds of the village easily fall into a kind of rural harmony. There is this difference between the noises of the town and those of the village; in the town the noises are numerous enough to lose their individuality, - except indeed in a few rather shrill and unpleasant cries; while in a village the sounds are generally independent, and follow each other in a kind of staccato movement, when not interrupted by long periods of silence. Of trees there is an abundance at Elstow, though no dense masses of wood mark the locality. But oaks of centuries and elms of respectable antiquity are scattered about all the roadsides and fields, besides a plentiful growth of smaller trees in orchards and hedges. Just now, the long leafless branches are thickening with the opening leaf-buds, and hiding the objects behind with a semi-green and semi-brown closing of the perspective. In this season which Tennyson has so charmingly designated the time that

“goes before the leaf,

When all the wood stands in the midst of green,

And nothing perfect”.

Elstow is beginning to don her summer screen, and to make herself invisible to distant eyes. And very soon the visitor will have to pass out of the fields where he has been listening to the lark and noting the sudden growth of the hedgeside plants, before he will be able to see more than the upper part of the solemn old church and two or three cottage roofs.

Houses in the High Street September 2007

What may be called the peculiar physiognomy of Elstow - for every village has its own individuality - is an air of being conscious that the eye of the stranger is upon it. A carefully preserved old-fashionedness, so to speak, clings about it. There are probably no houses that date back further than may be found in almost every village; but the old buildings are well-preserved, and there is little in the architecture of the street to suggest the present century, except it be the very evident repairs and restorations. Much thatch and many overhanging floors aid the gateway in the remarkable line of cottages near the middle of the village [Bunyans Mead], in giving the place an air of belonging to our grandfathers rather than to ourselves. But there is no appearance of dilapidation. Elstow has a character to maintain, and keeps a clean street and a neat outside for the visitor to look at; and I have seen nothing to suggest that this pleasing exterior is not complemented by tidy and comfortable interiors. It is perhaps easier for a lace village to be quiet and tidy than it is for villages where agriculture is supplemented by sources of income of a different character. A shoemakers’ village is often both dirty and unpicturesque, and is always the latter when it is not the former. A stocking-makers village is noisy, - at least the whirr of the frames is not a pleasant sound to the ear of the stranger who has no interest pecuniary or otherwise in the trade. But the bobbins as they quietly fly to and fro on the pillow make less noise than the good woman’s cheery chatter; and if the delicate texture is to be kept clean, there must be some attention paid to tidiness of hands and house.

![The Swan about 1900 [X373/596/7]](/CommunityHistories/Elstow/ElstowImages/The Swan about 1900 [X373-596-7].jpg)

The Swan about 1900 [X373/596/7]

The homesteads of the village have a substantial, but withal a cosy look. The two inns of the place are of the ordinary zoological character – the Swan and the Red Lion, the latter name most likely having a heraldic reference. The village can scarcely be said to have more than one street, the population of a little over 600 being housed on a long stretch of the road that runs directly north [sic south] from Bedford towards – nowhere in particular, except a village or two, until it reaches Luton. A few cottages have crept round the corner and located themselves on the road that runs westward; and a larger number, with a pleasant country house keeping them company, have arranged themselves round the spacious village Green. On the Green stands a short stone pedestal on a stone base, and is according to tradition the remains of a market cross. It looks as if it had last done duty as a sundial; and at present it does duty merely as a reminder of times and things that are obsolete. To Protestant England in these days of push and precision the market cross is a stumbling block, and the sundial altogether inadequate as a chronometer. On the Green also stands the Moot or Market House, known to readers of Bunyan’s biographies as the Green House. This place which is probably the most authentic memorial of Bunyan’s days extant in the village, has an appearance of neglect that is absent everywhere else. At least, there is a tumble-down air about the lower part of the building, through the broken walls of which boys and even men might get without trouble. The upper part of the building, however, is used as a school-room on Sunday afternoons, and as a preaching-place on Sunday evening.

Elstow Moot Hall September 2007

But the south side of the Green is the most interesting. The picture seen by the lounger on the low wall of the churchyard is singularly good of its kind. Beyond the old truncated elms that stand just inside the wall, lies the broad graveyard with its many stones, some of them hoary with lichens of nearly two centuries; and the background is filled in with the high and imposing nave and north aisle and massive tower, which make up all that now remains of a once magnificent abbey church. Non-aesthetic churchwardens, or indifferent vicars, or a stern Puritanism – perhaps all three influences at different times – have done a great deal towards robbing the building of its beauty in detail; but they have left the fine proportions of the outline, and nature with her kindly ivy has thrown a mantle such as artists love over some of the wounds in the old stone organism. In the clerestory, as seen from the graveyard, all the windows are walled up [no longer], but several of the Norman arches remain. The large windows in the aisle are Perpendicular, and could not have been parts of the original building. One of them is walled up, and was once partly covered by a small vestry, which was removed a few years ago. The north door, from which the north porch has been taken away, is a remarkably fine specimen of a Norman doorway, with a zigzag moulding peculiar to the Norman style. A strong iron staple fixed in the left jamb of the doorway is probably correctly held to have had female delinquents tied to it in days when penance had to be done in the church porch. Over the door is a bas-relief containing three figures, which are probably Jesus, Peter and John. The central figure is surrounded by that form of the aureole which is technically known as the Vesica Piscis, in shape an oval with acutely pointed ends. The figure has the right hand raised in the act of blessing. On its right is Peter with a key, and on its left John with a book.

Tympanum over the south door of the church September 2007

The tower stands about twenty feet from the church, and probably belongs to the same period as the Perpendicular windows. It is entered by a good doorway, with a square weather-moulding over a four-centred arch. The belfry windows are large and arranged in pairs. There are five good bells, all sound, placed in a single row from east to west. Not having seen any description of the church when I first visited it, I occupied some time climbing crawling around amongst the bells, in order to copy the inscriptions upon them. The following is the result of my dusty toil, beginning with the smallest bell near the west window: -

- 1. God save our king 1631.

- 2. Praise the Lord 1602.

- 3. Christopher Graie made me 1655.

- 4. ABCEEFG ABCDE RSTVW [all letters are upside-down]

- 5. Be yt knowne to all that doth me see, that Newcombe of Leicester made me 1604.

The bell tower February 2012

The second bell is the most ornate, and its legend instead of being in plain Roman characters as on the others, is in a kind of Church text. But the most peculiar legend is that on the fourth bell; indeed, it is unique in my experience. The workmanship of the legend must have been entrusted to a “prentice hand”. Not only is the idea of putting a few letters of the alphabet upon a bell a decidedly juvenile one, but the execution of the idea is equally juvenile. The appearance of the inscription suggests that broken fragments of a stamp containing the alphabet had been at three places impressed upon the soft mould in which the bell was to be cast. But the stamp was impressed the wrong way upwards; and, moreover, the letters on the stamp were so formed that the curve of the letters on the bell would stand on the wrong side. If the reader will rub a piece of writing paper on the following letters before the printing ink is dry, he will get an impression similar to that of the letters on the bell: ABCDEFG. I will leave him to think out for himself how they must have been arranged on the stamp which indented the matrix. In trying to reproduce the inscription above, the printer has been obliged to break a letter B as a substitute for a reversed R, since the ordinary type when turned would throw the curves on the wrong side of the straight stroke. From the same cause he has had to use a C for a reversed G.

Elstow Abbey from the east September 2007

Leaving the bells, I went to the roof, above the centre of which rises a small spire about a dozen feet high. The view from the old roof is wide and pretty. People too often forget that the most extensive views are as a rule to be obtained in comparatively level districts. Hills shut the spectator in an area which has a small radius; but a gently undulating wide river-valley gives a rich landscape fading away into the soft grey tints of the distant horizon. Why do not country gentlemen more frequently spend a little money in erecting ornamental towers for viewing the landscape from their grounds? On Elstow tower one is surrounded by a panorama such as cannot be seen from many natural eminences. If it could be seen from the terrace of a tourist’s hotel at some place of fashionable resort, it would be duly appreciated; but being close at hand, and easily obtainable, it is probably thought little of.

Remains of the Hillersdon Mansion February 2012

A low stone wall connects the tower with the church, and a door in the wall admits the visitor to a path which leads him to an interesting fragment of the early conventual building, founded by Judith, the much renowned niece of the Conqueror. A fine specimen of a polygonal Chapter House, with the vault resting on a column of Purbeck marble, is attached to the south side of the church, and is still in sufficiently good repair to be occasionally used. Before the Board School was built, this chapter house was sued for the purpose of a Sunday School; and it still retains a cupboard in which the School Library was once kept. It also contains a long table with inclined desks all round, which formerly stood in the church, and was used by the choir in the old days before the organ was built. Passing from the chapter house, the visitor finds himself among the ruins of a more recent building, dating from early in the 17th century. The principal doorway opens into the grass space on the south of the church through a fine porch which is still in good preservation, and which has the architecture above it completely hidden by an unusually dense mass of ivy. The mullioned rectangular windows of two or three rooms are still extant, and the ivy with which they are festooned gives them the picturesque appearance which is characteristic of ruins. The grassy space here is bounded by the little tributary to the Ouse that runs through the village; and among the lush green the cowslips are just now beginning to lift up their clusters of yellow bells. The church seen from this side is very uninteresting. The unaesthetic influences already referred to have been completely successful in stamping out all beauty of architectural detail.

Elstow Brook looking north-east February 2012

I find my paper is growing too long to allow me to give here the results of my visit to the interior of the church. I shall venture, therefore, to return to the subject in a future paper. The old building is full of a quaint interest that one misses altogether in new erections, and even in many of the “restorations” on which so much money is spent. “Restoration” is, I find, awaiting Elstow Church, and will be effected when the necessary funds are obtained. May the hand of the restorer be guided by a head that is judicious and a heart that feels a reverence for the too perishable relics of the past!

The interior looking east February 2012